Introduction

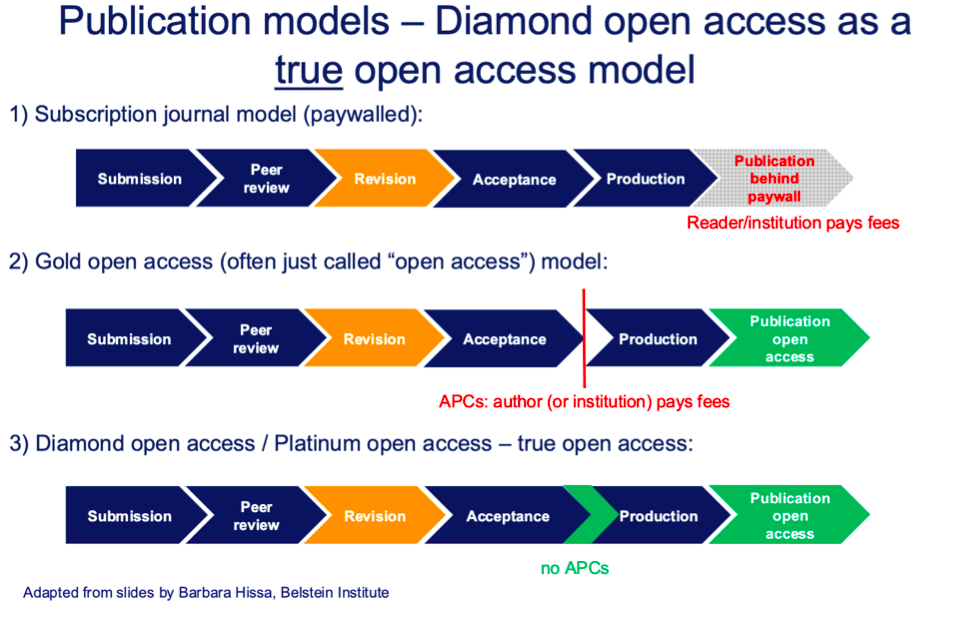

Scholarly communication needs to change because dominant publishing models are highly inequitable and expensive, to both authors and readers alike. While the concept of Open Access (OA) is often celebrated as a cornerstone of scientific progress and enables knowledge to be shared transparently, what does it really entail - and is it truly free of cost? In her talk on April 14th 2025, Prof. Dr. Martine Grice outlined several open access models, each with distinct implications for cost and accessibility. While all these models aim to make scholarly articles publicly available, they differ in who bears the cost - whether it’s the author, the reader, or a research institution.

Preparatory reading

The suggested reading for this particular session by Andringa (2024) argued that diamond OA counteracted systemic inequality. Contrary to other open access publishing models which benefit commercial publishers and rich countries, it supports system change towards a more equitable future and assures that open science is truly open for everyone.

📘 Journal Subscription Model 📘

In the Journal Subscription model, readers (or their institutions) must pay to access published research. Access is often limited to subscribers, which creates barriers for independent researchers or institutions in the Global South. Authors typically do not pay to publish, but also do not profit from their work, the revenue goes to the publishers. Peer review and editorial services are funded through subscription fees, often with high profit margins for commercial publishers.

Examples: AAA - Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Kodikas / Code

🟢 Green Open Access 🟢

In the Green OA model, authors publish their work in subscription-based journals but are allowed to self-archive a version (usually a preprint or postprint) in institutional repositories or on personal websites. Access is allowed, but often delayed or restricted to a less polished version.

Examples: arXiv, Kölner UniversitätsPublikationsServer, HAL Open Science

🟡 Gold Open Access 🟡

In the Gold OA model, the article is made freely available immediately upon publication. However, the cost is shifted to authors (or rather their institutions) through Article Processing Charges (APCs), which can amount to thousands of euros for a single article. Plus, APCs lead to a different threat to scientific integrity: the standards for acceptance of articles can quickly become lax due to commercial publishers’ profit motive.

Examples: Frontiers in Language Sciences, PLOS ONE

💎 Diamond (Platinum) Open Access 💎

The Diamond OA model - what Prof. Grice called the “true open access” - allows articles to be freely accessed without charging authors or readers. Costs are usually covered by institutions, libraries, or consortia.

Examples: Glossa, Language Science Press, STAR, Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft

Some journals have already transitioned from a subscription, a hybrid, or a gold OA models to the diamond model. In some cases, the members of the editorial board (who are always academics in the field) of an established journal resigned and founded an alternative, diamond OA journal (e.g., going from Lingua to Glossa). In others, the academic society that owns the journal decided to switch model, as in the Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft owned by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sprachwissenschaft (German Linguistic Society) that moved from a commercial for-profit publisher to a non-profit institutional publisher. According to Bosman (2021), most diamond OA journals are scholar-led and sustainable, many having been in existence for decades with very low running costs.

Discussion

In the discussion, Prof. Grice highlighted several critical issues with non-diamond models. One major concern is that the high fees charged to either readers (in subscription models) or authors (in gold OA) are not necessarily proportional to the actual labor or costs involved in the publishing process. The commercialization of scholarship may also compromise academic integrity. Scientists might feel pressured to produce exciting or exaggerated results in order to get published in high-impact journals.

The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) is a free and open index of open access journals from 136 countries and 89 languages. You can search for journals, articles, and metadata by keywords, categories, or filters, and learn more about DOAJ’s mission, support, and community: https://doaj.org/.

Applied linguist Ali H. Al-Horrie has compiled and continues to update a (non-exhaustive) list of diamond OA journals in applied linguistics: https://www.ali-alhoorie.com/applied-linguistics-open-access-journals.

Conclusion

In summary, Prof. Grice suggested that the diamond model currently represents the most equitable approach. It promotes inclusive knowledge access, supports marginalized communities, removes financial barriers and contributes to the decolonization of scholarly communication. At the end of the day, science should promote scholarly exchange without obstacles, so that open science becomes as universally accessible as its name implies.

(“Diamond Age” by jurvetson is licensed under CC BY 2.0).