Setting the Scene: Reproducibility in Action

The last session of ReproducibiliTea in the HumaniTeas took place on June 23rd at 5:45 p.m., featuring Marie Flesch from the Laboratoire de Linguistique Formelle at Université Paris Cité. In this session, Marie Flesch presented concrete workflows, design choices, and editorial processes that can contribute to accessible and reproducible teaching materials based on her experience as the managing editor of the French version of the open-access initiative Programming Historian (PH). This session explored how Programming Historian uses a peer-reviewed course format supported by a well-structured editorial and technical framework to promote openness, multilingual publication and a strong sense of community, highlighting how this approach ensures that digital humanities educational materials remain transparent, accessible, and up-to-date.

Behind the Screens: Insights from the Programming Historian

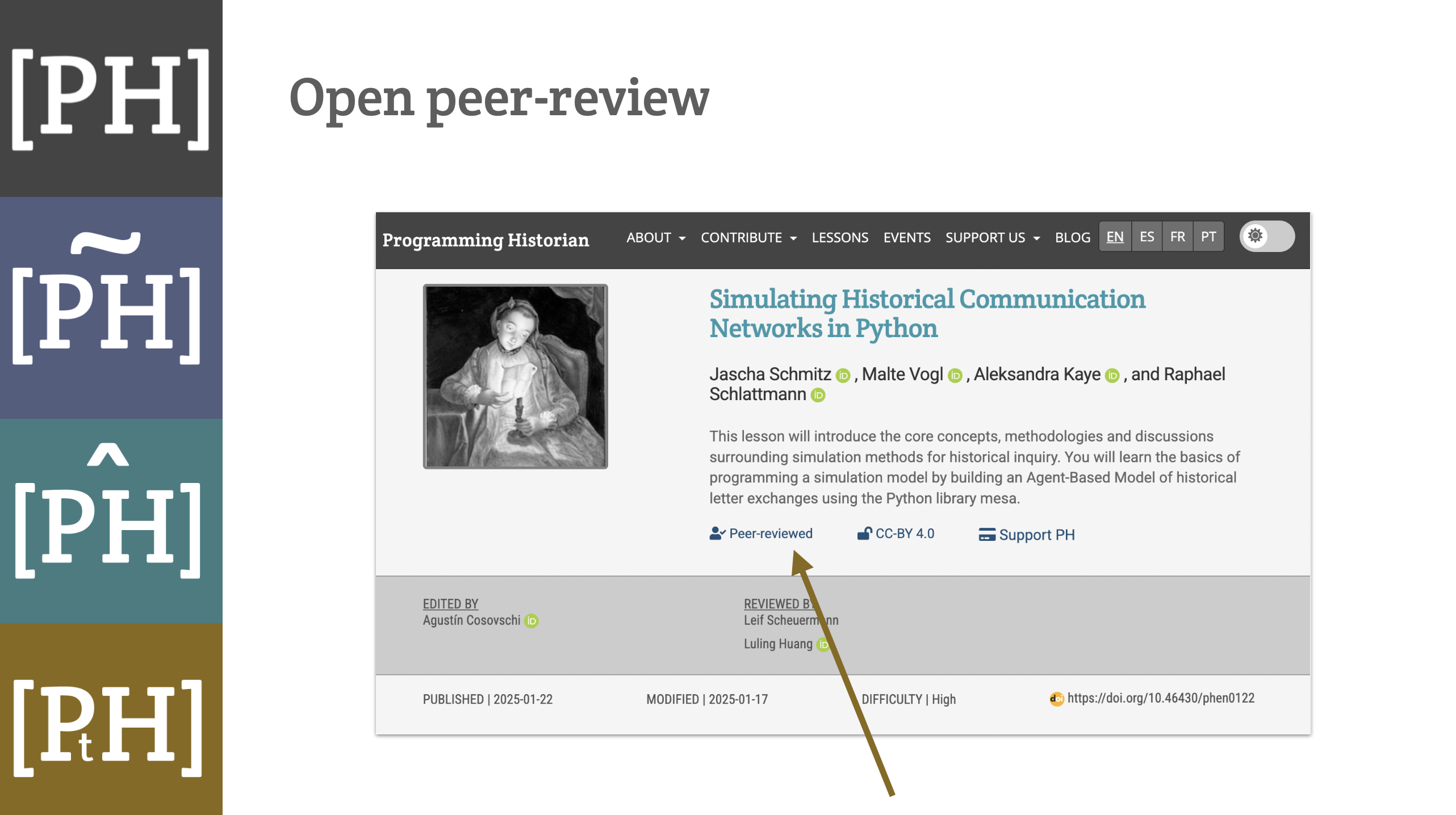

Marie Flesch, Managing Editor of Programming Historian en français, presented “Reproducibility in the teaching of Digital Humanities: Lessons from Programming Historian”. Flesch explained that the platform’s open peer review system on GitHub creates transparency, allowing the public to view all editorial conversations. She explained that this approach encourages reviewers to provide detailed and helpful feedback, as their comments are public. This shift away from anonymous peer review creates accountability while fostering a collaborative community atmosphere and ensuring that peer reviewers are credited for their contributions.

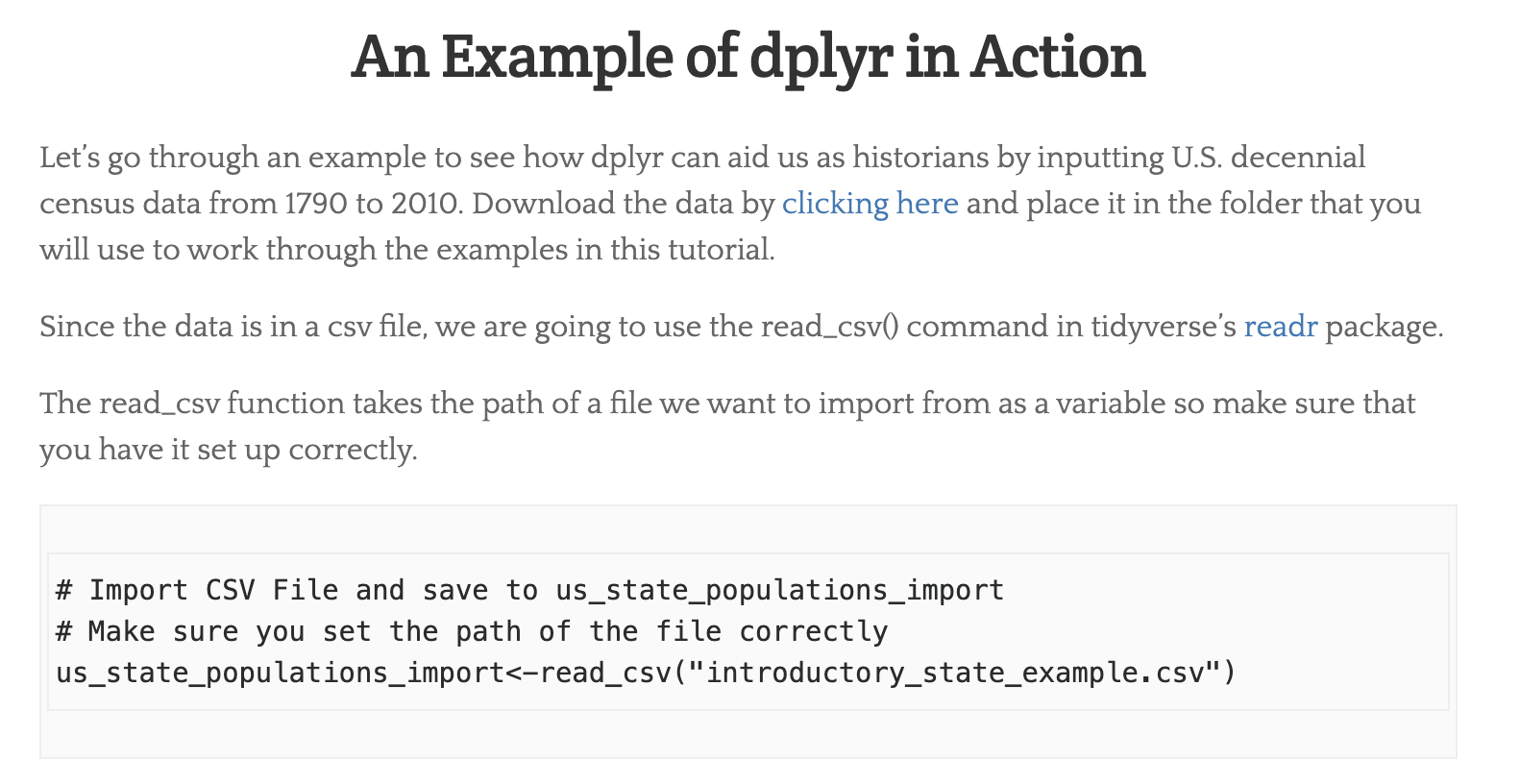

Flesch talked about the platform’s commitment to multilingualism, emphasizing the importance of making computational methods accessible to non-English-speaking communities. Later, the challenges of maintaining lessons in multiple languages and adapting content for different audiences, such as the need to rework lessons for French-speaking users with relevant datasets was discussed. The talk also explained the structure of Programming Historian lessons. In contrast to typical tutorials, these lessons include methodological reflections, alternative solutions for various data formats, complete bibliographies, and authentic research data sets, allowing you to copy code chunks and work on your own computer. This structure connects practical instruction and encourages critical thinking and reproducibility in digital humanities education.

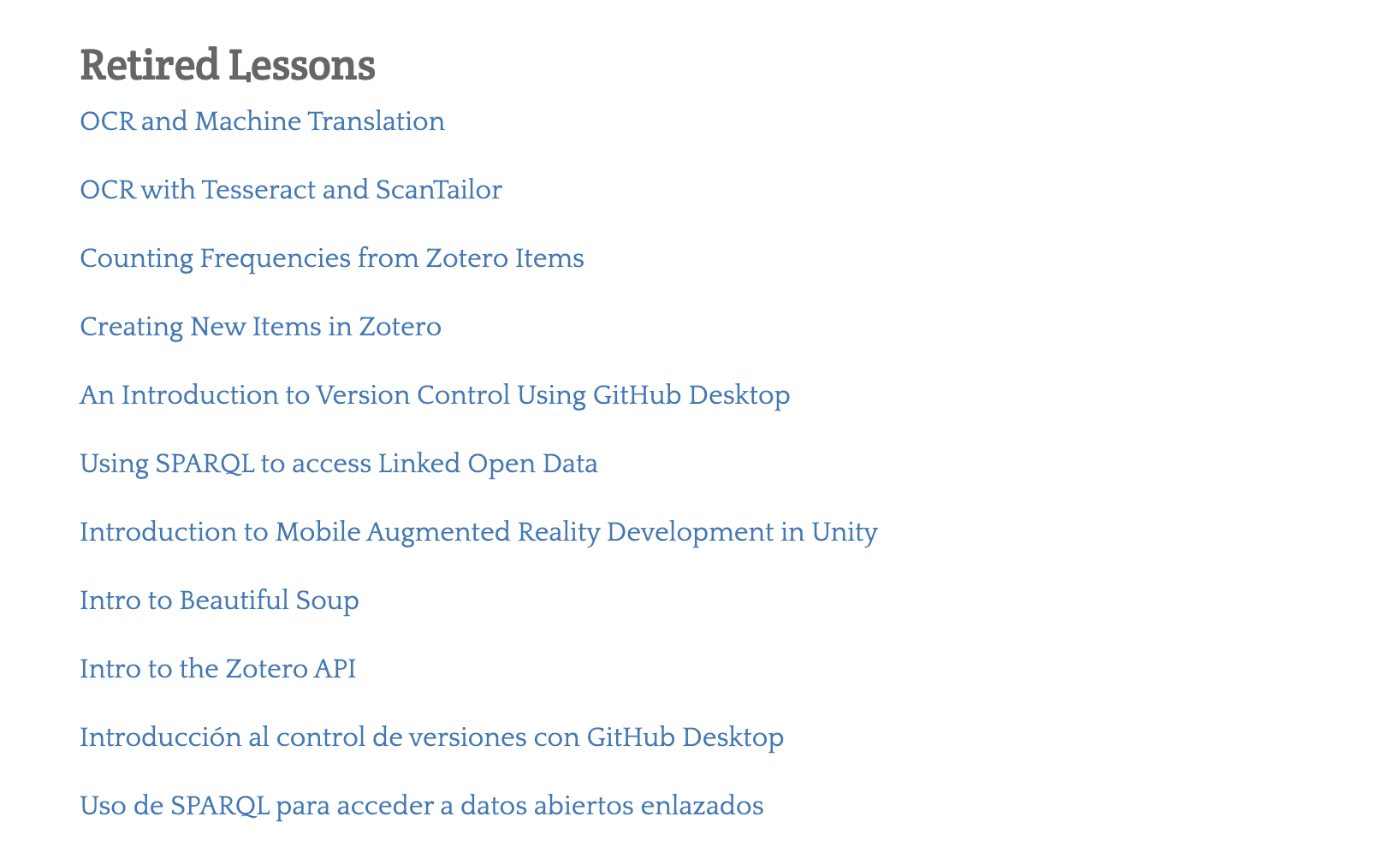

Flesch also talked about ongoing challenges, such as the “retirement policy” for outdated lessons. For example, after Twitter restricted API access, Programming Historian added a prominent warning to their Twitter API lesson. They noted that it is no longer fully reproducible, though it is still useful for those with existing tweet datasets. Instead of retiring lessons right away, the team warns readers and does its best to update content, if possible. This commitment to transparency is clear through the warning banners and editorial notes on the website.

Debates & Discoveries: Lessons from the Discussion

The discussion segment of the session brought to light several key issues and ongoing debates central to the Programming Historian project and, more broadly, to digital humanities education.

Radical Transparency in Peer Review

A central and important topic was the platform’s commitment an open peer review system. When asked whether the review process was anonymous, Marie Flesch clarified that it is entirely open from the outset—everyone involved knows each other’s identities. Making this process transparent is meant to encourage accountability and constructive feedback. It also directly addresses common criticisms of traditional, anonymous peer review systems. The open process builds trust and encourages a collaborative and community-driven approach to improving educational resources.

The Naming Dilemma: “Programming Historian”

Later, there was a discussion about the ongoing challenge of the platform’s name. Participants questioned the relevance of “historian” in the title, given the project’s broad, interdisciplinary scope. Flesch noted that the title no longer accurately reflects the diversity of contributors and users, the majority of whom are not historians. Despite the annual internal debates about re-branding suggestions, alternatives such as “Programming Humanist” have not met general approval yet. The team remains tied to the established brand, particularly in light of its recognition as an established, high-quality publication outlet in the U.S., Spain, and Latin America. However, in countries like France and Germany, the name can act as a barrier, as potential users outside the field of history may overlook the resource. This persistent identity question underscores the conflict between brand legacy and inclusivity in academic projects.

Sustainability and the “Retirement Policy”

Another inquiry pertained to the sustainability of lessons in the face of rapidly evolving digital tools and platforms. One of the participants expressed concerns regarding the “retirement policy,” questioning whether the retirement of outdated lessons might potentially compromise the platform’s value, considering the ongoing evolution of APIs and data sources. Flesch explained that the team is cautious about retiring content, so, as of yet, only about 11 out of more than 200 lessons have been retired. This process is not taken lightly, as each lesson represents significant work by authors, reviewers, and translators. In circumstances where it is possible, lessons are adapted for new contexts; for example, a Twitter API lesson for French users was translated and updated. However, it was also mentioned that this often requires substantial effort, sometimes amounting to a complete overhaul.

Adaptation and Cross-Referencing

Furthermore, participants proposed strategies to extend the life of lessons, including cross-referencing with newer, related lessons. Marie Flesch confirmed that these practices are already in place where feasible. However, she acknowledged the occurrence of circumstances in which the updating of lessons becomes unfeasible due to fundamental changes in external platforms or data, highlighting the ongoing need for flexible editorial strategies.

Open Questions & Future Directions

The session was highly informative, providing a more advanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities in teaching reproducibility within the context of digital humanities. As it was also reflected on the discussion, a few key questions emerged that may shape future conversations on reproducibility in digital humanities:

What is the future of multilingual accessibility in digital humanities?

As mentioned earlier, Programming Historian’s multilingual approach increases accessibility. However, updating and maintaining courses in multiple languages is resource-intensive. How can these efforts be scaled ina more sustainable way?

Can transparent peer review reshape academic publishing and how can we ensure transparent peer review becomes standard practice?

The open peer review model encourages accountability. Could this approach be adopted more widely, and what challenges might it encounter in traditional publication outlets for academic research?

What features or support would make digital humanities tutorials more accessible and sustainable for you and your community?

References

Programming Historian. (n.d.). Programming Historian. https://programminghistorian.org/

Quinn, M. (2021, July 20). Data wrangling and management in R. Programming Historian. https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/data-wrangling-and-management-in-r

Morrissey, K., Milligan, I., & Morton, A. (2021, September 20). A beginner’s guide to working with Twitter data. Programming Historian. https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/beginners-guide-to-twitter-data

Programming Historian Editorial Team. (2023). Lesson retirement policy. Programming Historian. https://programminghistorian.org/en/lesson-retirement-policy