Preregistering qualitative research: what, why, and how?

A quick refresher: What is preregistration?

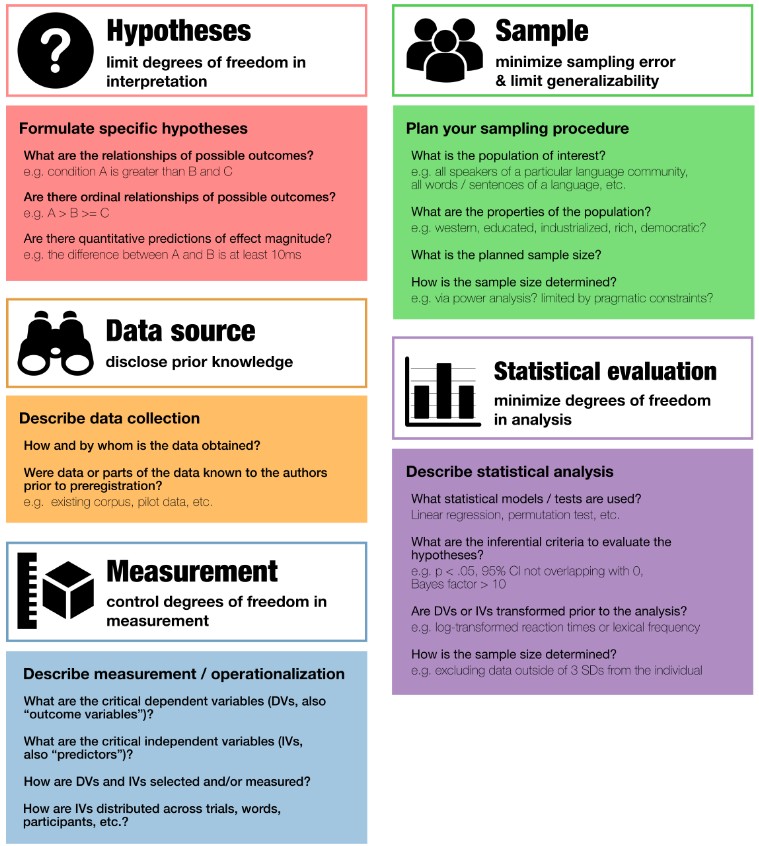

Preregistration involves creating a time-stamped document in which researchers specify how they plan to collect their data and conduct their analysis. This process encourages researchers to define their research questions and analysis plan before observing the research outcomes and distinguishes analyses and outcomes that result from prediction from those that result from postdiction (Nosek et al. 2018).

Preregistration has been designed for and principally employed in quantitative studies in order to fix problems of hypothesis testing and statistical inference (such as HARKing and p-hacking), thus making studies more transparent and credible. It does this by drawing a clear line between the exploratory and confirmatory parts of a study thus reducing researcher degrees of freedom as the study is committed to the specified analytic pipeline before observing the data (Nosek et al. 2018, 2601). Additionally, public preregistration can help to reduce publication biases, as the number of failed attempts to reject a hypothesis can be explicitly tracked (Roettger 2021, 1234).

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with exploring the how, why, and what of human experiences, often through rich, language-based data. As Haven & Van Grootel (2019, 232) explain, this kind of research frequently relies on interviews, focus groups, or observation to gather insights, aiming to uncover the lived perspectives of participants. Rather than being constrained by rigid structures, qualitative designs are typically flexible and emergent, which is a characteristic that, far from weakening the study, “can strengthen and deepen the rigor and validity of the qualitative study, instead of undermining” (Haven and Van Grootel 2019, 232).

Though it is guided mainly by postdiction logic, this methodological approach can still incorporate elements of prediction in its design (Haven and Van Grootel 2019, 233). Flexibility is especially important within this postdictive framework; as the authors note, “in qualitative research following a postdiction logic, flexibility is an invaluable asset” (Haven and Van Grootel 2019, 234).

Moreover, qualitative research embraces the inherently interpretive role of the researcher. The researcher is not a detached observer but rather “functions as part of the measurement instrument itself, and has a great say in generating findings from the data” (Haven and Van Grootel 2019, 234). Every finding, then, is not an objective truth but an interpretation—shaped by the researcher’s lens and the subjective nature of the inquiry itself.

Should I preregister my qualitative study?

Preregistration makes explicit what was hypothesised before an analysis, which findings were in the line with those hypotheses, and which weren’t. Thus, in their standard design, they are most suited for confirmatory hypothesis-testing. For qualitative research, which has an exploratory nature, some have argued that preregistration is unnecessary (Coffman and Niederle 2015; Humphreys, Sanchez De La Sierra, and Van Der Windt 2013).

However, making hypotheses explicit is only one feature of preregistration and such a view overlooks the broad utility of preregistration, according to Haven & Van Grootel (2019, 236) who see inherent usefulness in putting one’s “study design and plan on an open platform for the scientific community to scrutinize”. Even in the absence of formal hypotheses, a qualitative study always has clear aims, motivations, and methodological decisions, each of which can and should be made transparent through preregistration.

Critics also argue that because qualitative designs are flexible and evolve over time, preregistration is too rigid to be meaningful. Yet, this argument does not hold, because “it is perfectly possible to specify a qualitative study’s design without disrespecting the flexibility of the qualitative research” (Haven and Van Grootel 2019, 236). Even in quantitative research, deviations from the preregistered plan are permissible “as long as the motives for diverting are justified and transparently communicated” (2019, 237). In the same spirit, qualitative preregistration should be treated as a “living document” (2019, 237), not a static one, allowing researchers to update it with rationale for changes. This approach, including multiple “freezes” of the preregistration, can enhance transparency by enabling readers and reviewers to trace the study’s development.

A third common objection claims that the inherent subjectivity of qualitative research renders preregistration meaningless. However, this view, as Haven and Van Grootel (2019, 237) assert, “is – we believe – mistaken” as it actually “makes the preregistration more useful”. Because objectivity is not the aim in qualitative inquiry, where “every qualitative researcher has, and needs, her own philosophical paradigm and theoretical values that influence her interpretation of the data”, preregistration offers a unique opportunity (2019, 237). It allows researchers to make explicit which tradition and theoretical lens they work from, fostering critical reflection on one’s values before data collection begins. This practice not only aligns with the epistemological stance of qualitative research but also, as the authors argue, “could possibly enhance the credibility of qualitative research” by clarifying the interpretive lens used (2019, 237).

Finally, some argue that preregistration does little to increase the credibility of qualitative studies. On the contrary, Haven and Van Grootel (2019, 237) emphasize that “credibility is strengthened when the analyses form a solid basis for the conclusion he/she presents”. A preregistered design allows others to evaluate whether appropriate data collection and analysis methods were chosen, and whether the interpretations are convincingly grounded in the data. This speaks to key criteria of qualitative rigor, dependability and confirmability, as defined by Lincoln and Guba (Lincoln and Guba 1985). By documenting decisions transparently and justifying methodological shifts, preregistration supports these standards and invites more robust, informed engagement with the research.

In sum, while preregistration presents challenges for qualitative research, it is not only feasible but also beneficial so YES, you should preregister your qualitative study!. Rather than undermining qualitative principles, it offers a structured way to enhance transparency, encourage reflexivity, and strengthen credibility, without sacrificing the methodological richness and flexibility that define qualitative inquiry.

If you want to read another good blog post about qualitative preregistration, check out this one from the Centre for Open Science by some of the people we’ve mentioned here.

How do I preregister my qualitative study? Let’s look at some templates.

If you would like to specify key aspects of your qualitative study and analysis details and decisions before conducting the bulk of the research, there is an OSF qualitative preregistration template available. There are also other templates available, such as this one by Tamarinde L. Haven and Leonie Van Grootel.

The main difference between quantitative/standard preregistration and qualitative preregistration is that the former serves to clearly delineate between the confirmatory and exploratory parts of a study whereas the latter functions more like a plan for the researcher(s) and a potential guide for their reader(s) into the development and reasoning of their exploratory study. As we can see in the comparison between the OSF standard and qualitative preregistrations, questions about variables and confirmatory (statistical) analyses are not included but more detail about the exploratory analysis is asked for in the qualitative preregistration than in the quantitative one.

So now once you have a research question in mind, a plan for how you’ll collect data to investigate it, and an analytic approach for interpreting the data, you are ready to preregister your qualitative study!

| OSF Standard Preregistration | OSF Qualitative Preregistration | |

|---|---|---|

| Study information | Hypotheses | Research aims Research question(s) Anticipated duration |

| Design plan | Study type Study design |

Study type/design |

Blinding Randomization |

||

| Sampling plan | Sample size Sample size rationale |

Sampling and case selection strategy |

| Data collection | Existing data Explanation of existing data |

|

| Data collection procedures | Data source(s) and data type(s) Data collection methods Data collection tools, instruments, or plans |

|

| Stopping rule | Stopping criteria | |

| Variables | Manipulated variables Measured variables Indices |

|

| Analysis plan | Statistical models Transformations Inference Criteria Data exclusion Missing data |

|

| Exploratory analysis | Data analysis approach Data analysis process Credibility strategies + rationale |

|

| Other | Miscellaneous |

If you want to read more about quantitative pre-registration, click here.

To learn more about the questionable research practices that pre-registration provides a strategy for countering, check out this great zine